If you’re curious about the type of effort required to grow plumeria, you’ve come to the right place.

Who wouldn’t want this wonderful specimen in their landscape? Also called frangipani, it’s worth the effort to bring home its bright, stunning flowers and interesting texture, but you may be pleased to learn that the work required is minimal.

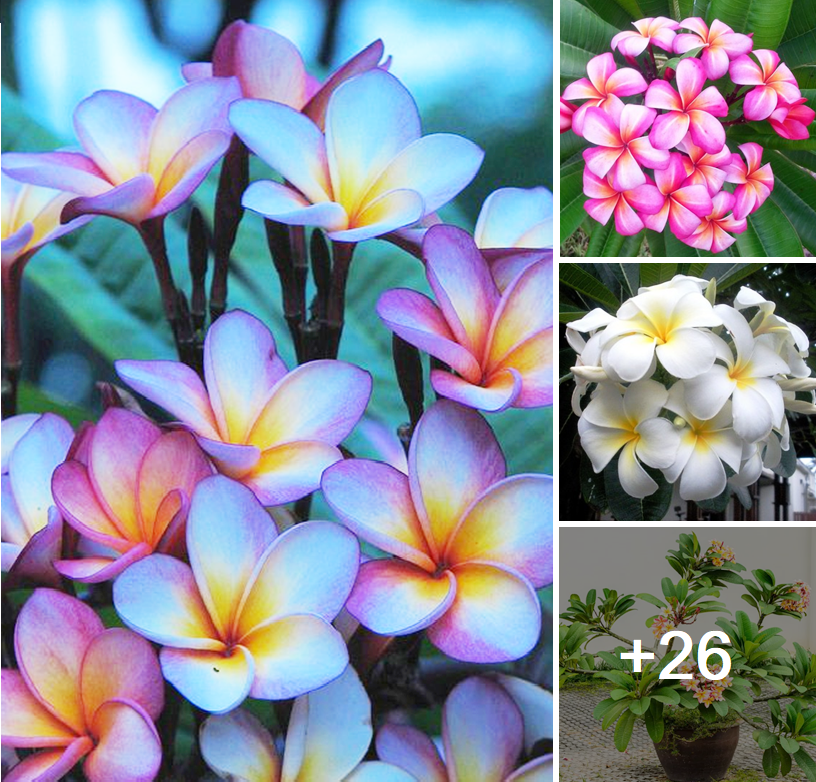

A close-up vertical shot of white and yellow Plumeria (frangipani) flowers growing in the garden with foliage in soft focus in the background. To the top and bottom of the frame there is green and white printed text.

We link to suppliers to help you find relevant products. If you purchase from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

We’ll cover all the details of this shrub or small tree—including varieties to choose for growing in containers so they can grace your garden with flowers that add lingering aroma and stunning beauty, no matter where you live.

A vertical close-up shot of frangipani flowers growing in the garden with dark green foliage in the background.

Currently, there are 11 accepted species in the genus, although there are others that are under debate, with hundreds of additional known cultivars and hybrids.

Species of this genus are native to Central America and the West Indies where they grow in forests as understory trees.

A horizontal shot of a frangipani tree growing in the garden depicted in bright sunshine.

Because of their relatively compact size, large leaves, and showy flower clusters, they have become common landscape plants in southern Florida, Texas, California, and the Hawaiian Islands, as well as many other parts of the world.

Their flowers are often recognized as a symbol of the tropics. And there is some confusion about where these plants originated, as many mistakenly believe they come from Hawaii due to the historical use of frangipani flowers to make leis.

Frangipani is not found in the wild in Hawaii, but there are several breeding programs there that still produce new varieties.

Anatomy

The most common species produce slightly overlapping, pinwheel-shaped, waxy flowers in shades of white, yellow, pink, orange, apricot, red and magenta. Petals can be rounded or pointed, fluted from tubes that sometimes appear in contrasting colors.

A close-up horizontal shot of a cluster of white and yellow frangipani (Plumeria) flowers with foliage in soft focus in the background.

Some varieties produce shell-type flowers. These have petals that are folded more tightly than the open types and they sometimes have contrasting stripes or bands, for example in the variety called ‘Madras White Shell’.

Some less common species, such as P. stenopetala, produce flowers that have thin, long petals that radiate from a central tube. Their leaves also tend to be narrower and they don’t root well from cuttings, so they are harder to find for sale.

In subtropical regions, such as USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 9 through 11, buds begin to appear in March and April that will open until October or November.

Flowers are usually two to three inches in diameter, and sometimes have contrasting centers – like the white flowers with yellow centers of P. alba, which is one of the most easily recognized species.

However, there are some tones that are less common, such as a deep magenta that looks purple and a deep red that is sometimes called black, as in P. rubra ‘Scott Pratt Volcano’ or ‘Kohalo’. species produce deep red blooms that can darken to appear almost black at high temperatures.

Their scent is stronger in the evening to attract nocturnal pollinators. But there is a catch.

A close-up horizontal shot of frangipani (Plumeria) flowers covered in water droplets with a moth on the petals.

Plumeria are tricksters. They may be beautiful, but to pollinators it is a cruel beauty. The strong fragrance produced by the blossoms attracts bees, butterflies and moths, such as sphinxes and hawkmoths, to get a taste of nectar – only to find that there is no nectar to be had.

Instead, the moths shake pollen free from the self-pollinating flowers where it falls to exposed stamens on the flowers below, thus pollinating the plant without returning to the moth.

Thrips and ants are also known to pollinate the flowers when they crawl into the exposed tubes of the carriers.

Pollinated flowers of some specimens produce horn-shaped pods in shades of green, brown, rust, etc